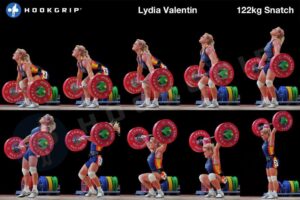

The Olympic Snatch is one of the most complicated and effective weightlifting movements that is frequently used in sports performance, CrossFit, and barbell sport.

The Snatch itself involves Lifted a barbell from the ground to the overhead position in one motion. Traditionally, the snatch is caught deep in a squat position requiring a significant amount of upper-body stability and lower body mobility.

Part of what makes the snatch such a unique lift is that any small deviation from proper technique and mechanics can result in a missed lift. For other major lifts in the super total such as the deadlift, Clean and Jerk, and Squat, small deviations can be compensated for by strength and grit. This is why the Snatch is called by some “the most athletic movement in Olympic Sport”

The snatch itself is typically broken down into three primary phases; the first pull, the second pull, and the catch.

The First Pull:

The First Pull:

During the first pull, the barbell is lifted off of the ground up to the crease of the hip. Within the first pull, the knees are pulled back to make room the barbell around the knees and then return forwards as the bar is brought towards the crease of the hip.

The physical demands of this position include primarily proper thoracic (upper/middle back) extension, foot stability, and the ability to appropriately load the hamstrings.

While there is much debate as to the appropriate torso height for the liftoff phase of the snatch, most coaches will agree that a rounded upper back is an efficient position to pull from, which means that some level of thoracic extension, without composing the neck or lower back is ideal.

Additionally, the ability to stabilize the arch of the foot is critical for the liftoff phase as the foot is to be in full contact with the ground and any deviation away from the balanced position can result in a missed lift or injury, particularly when the weight increases relatively to your max. Most lifters also use an Olympic weightlifting shoe designed to improve dorsiflexion capacity of the ankle, though at times at the expense of a properly centered foot and stabilized arch.

The initial lift of the bar during the snatching from the ground up to the top of the knee requires a proper hip hinge during which the hamstrings and posterior chain are adequately loaded to produce maximal force and reduced the compressive load on the spine while lifting the bar. Likewise, the bar is taught to be kept very close to the body to reduce strain place on the lower back during the lift.

The Second Pull:

Once the bar has reached the top of the thigh or hip crease, the second pull is initiated in which the body uses triple extension (hip, knee, ankle) to propel the bar vertically. Once the bar has reached the maximal height, the lifter descends into the catch position to receive the barbell.

Athletes vary in at which point they initiate the second pull. Some athletes chose to extend just before the bar reaches the crease or the hip but the majority of weightlifting coaches teach the lifter to be patient during the first pull and explosively triple-extend once the bar reaches the hips in the snatch. An early second pull can result in an inefficient bar bath and potentially a leak of potential vertical force to propel the bar upwards.

Important characteristics for the second pull are more related to training athletic qualities and synchronizing extension of the hip, knee, and ankle. From a mobility and motor control standpoint, however, the ability to properly extend the hip while stabilizing the spine is arguably the most important physical characteristic for executing an efficient and safe second pull.

Hip Extension is not only an important motion for the snatch, but also a variety of fitness movements including the deadlift, running, bridging, and lunging. Often individuals possess very little hip extension and use their lumbar spine (lower back) to extend during a lift or athletic movement. When we can effectively address pure hip extension, through manual therapy and specific exercises, we can expand your force capacity as well as significantly reduce the likelihood of a lower back injury.

The Catch:

After the lifting drops under the barbell following the second pull, the catch position requires the lifter to have two feet planted on the floor and the arms locked out overhead. Once the lifter catches in a stable position and stands up to the standing position.

The “catch” phase of the lift is by far the most physically demanding in that it requires a tremendous ability to sit into a deep squat with an upright posture and lock the arms out overhead. The squat itself has numerous prerequisites that we will cover in a later installment of this series, but the difference during this lift is that the squat is required with a barbell locked out overhead. A traditional powerlifting squat has very little upper body mobility requirements beyond enough shoulder rotation to hold the bar. The front squat does require a relatively upright torso as well as upper body extensibility for the front-rack. However, neither of these compare to the demands of the overhead squat.

To catch the barbell in a stable enough position to stand up and maintain a successful lift, the shoulder complex must have a tremendous degree of overhead stability coupled with adequate upper back extension to take the strain off of the shoulder joint itself.

Additionally, a physical capacity that is not talked about frequency is the ability of the wrist to radially deviate (bend towards the thumb side). Generally, at higher levels of Olympic weightlifting, lifters will grip very wide on the bar to both meet the hip crease during the second pull and reduce the overhead mobility requirement during the catch. Because the wrist is a small and complex joint, we mustn’t place the wrist in a vulnerable position during the snatch.

Common Injuries Seen in the Snatch

- Patellofemoral syndrome

- Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

- AC joint sprain/strain

- Cervical Disc Herniation

- Wrist Strain

If you are a Crossfitter, Olympic weightlifter, or other athlete and would like a joint-by-joint injury risk assessment as well as therapy to correct these findings, please reach out to us at 754-231-8338, we would love to help you!